A talk given by Malcolm Green at Alastair Brotchie’s Funeral, 20 February 2023

Foreword

Alastair Brotchie was founding editor of Atlas Press (1983 to 2023). This personal and totally ‘Atlas’ speech, from Alastair’s co-founding editor, Malcolm Green (Red Sphinx), captures the man and the imprint. It’s full of inspiration, anecdotes, fascinating history and brilliant energy.

For the last decade Atlas Press has taken part in Small Publishers Fair most years and in 2017 Alastair organised a celebration for the imprint’s 35th birthday on the Friday night so publishers and others around for the Fair could go. As we celebrate the imprint’s next milestone with the exhibition Forty Years of Atlas Press we also mark the loss of Alastair. We will miss him. We will remember him.

Helen Mitchell, Small Publishers Fair organiser, September 2023

I have been asked to talk about Alastair and our publishing activities, but I must add that he was not only a writer and publisher, but also a fine artist, as we shall see. We met in autumn 1970, during our first week at Reading University, and hit it off at once. He showed me his book collection, including beautiful works illustrated by Harry Clarke, and he introduced me to Alfred Jarry, who he said had kept him sane while at boarding school. But intriguingly, he was already combining fine art and books in handmade editions consisting of his own images and texts by Aleister Crowley, all done by means of linocut.

Alastair also worked on some related projects while at Reading, such as The Art Exchange Anthology for the art department society, edited by him and Graham Challifour, and circulars for related events, which featured not only Alfred Jarry in translations and images, but also renaissance style graphics and a highly irreverent logo that foresaw much of the irreverent humour and the look of Atlas Press. Publishing was still ten years away, but already it was gestating.

Our own collaborations began around 1973, when we planned to produce a book we thought we could sell to a publisher. I forget the name, the lists we drew up have been lost, but the subject was the uncelebrated things famous people got up to on the side. As for instance H.G. Wells, a war game strategist who made tin soldiers, and many others like that. The project floundered, but it kept us in contact over the next few years when I moved to Nottingham in summer 1973. We wrote and visited one another, and with distance our friendship deepened.

A few years later we were sharing an Acme house in London. But before that, a key event occurred that was directly connected with Atlas. Phil Jenkins, who also appeared in early Atlas Anthologies, gave me a copy of Harry Mathews’ writings. I read it, was staggered, and told Alastair, who, after nicking and reading my copy – I never saw it again – was equally staggered. So when in 1982 he asked me if I wanted to help do a “literary magazine,” as he termed it, it was clear that Harry would be included. His name was top of the list on the cover, not simply because he was the one living author we had at that time. That would be unfair on Harry. As Alastair wrote to me, Harry had been so encouraging and forthcoming when told about our vague plans that Alastair realized we were now committed to carry on, which we did for 40 years.

The literary magazine, Atlas Anthology 1, became numbers 2 & 3, followed by 165 other titles up until 2021. With time, Atlas began to look like a proper publishing house, not least thanks to Alastair’s way of charming and enlisting the services of rare and wonderful people. The English surrealist and poet David Gascoyne agreed to translate The Magnetic Fields by Breton and Soupault, our first book, and the celebrated translator Barbara Wright did the same for Pierre Albert-Birot’s Grabinolour, (she was delighted that anyone even knew of Pierre Albert-Birot, let alone wanted to publish him, and later did us proud with several Queneau titles).

No less importantly, Alastair found two additional directors, Antony Melville and Chris Allen, who thankfully raised the production standards etc, and put us on a professional footing. With time he attracted a host of marvellous translators, writers, helpers, in short: enthusiasts for enthused writing

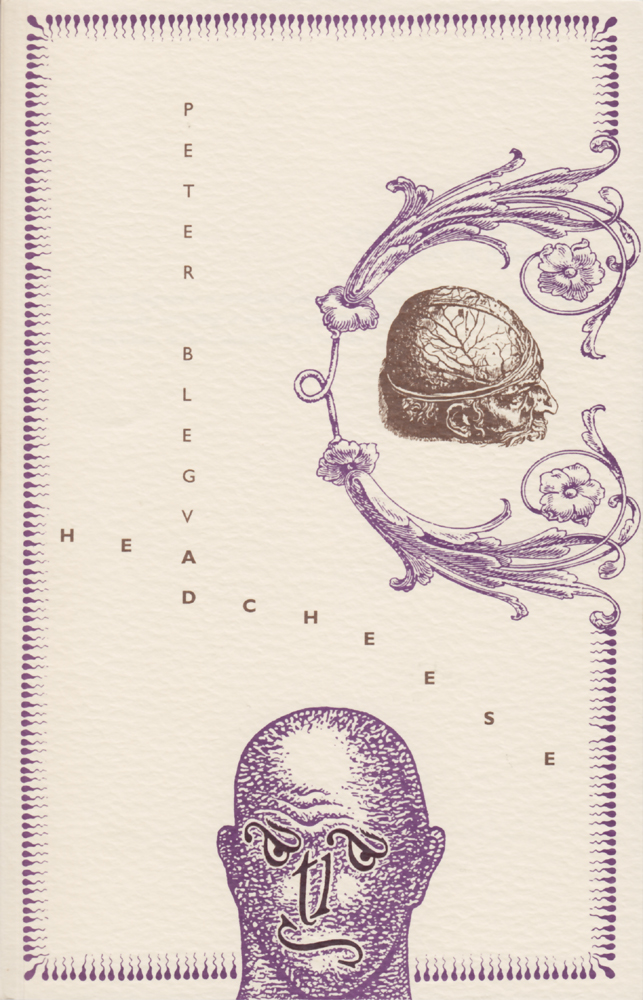

But once again I must stress that Alastair was a fine artist, who even participated in the British Pavilion at the 1986 Venice Biennale. So while we drew up lists of potential authors and titles, Alastair also tinkered away at new series, new visual devices, and a constant barrage of leaflets and propaganda, with the artist always shining through. First of all, Alastair’s full-colour silkscreen cover for Anthology 1, printed by Janey Colling, showing a Hamlet-like skeleton holding a globe in one hand and studying it down a telescope. Then the funny faced Atlas Head for the cover of the Printed Head series – “printed head” being a literal translation of tirage de tete or luxury edition in French – with its features made up of the letters A-T-L-A-S – the two ‘a’s as the eyes, the ‘s’ as a scowling mouth, and so on. Not to forget the sperms on the borders of our books, which denoted them as seminal works, and the @las logo, another pun which, with the addition of four letters more letters spelled “@lastair”!

These visual and linguistic puns often brought Alastair back to his early linocut aesthetic, no doubt inspired by Alfred Jarry, an acclaimed innovator in woodcuts, and which Alastair also liked to use to advertise gallery and theatre shows. Most strikingly for Atlas are the painfully punning images for the cover of the ArkHive series in 1993: an ark to archive and convey our archaeological finds – by then we saw ourselves very much as literary excavators, digging up writing which for years had been covered with the dust of indifference; then a beehive, a mellifluous place of warmth, storage and industry – almost Beuysian, one might think, except of course we were far more interested in sacred conspiracies and the Great Game than soppy Anthroposophy. Atlas was about the naughty boys of art and writing, the Dieter Roths, Georges Batailles, the Actionists et al. and as Alastair said, we had to brand ourselves as the naughty boys of publishing.

So while Alastair was as an aesthete, as evinced by the sheer elegance of the iconic square-shaped books in the anti-classics and Eclectics series, artistic finery sometimes made way for glorious brashness and mischievous humour, such as in the cover for Breton & Eluard᾿s Immaculate Conception – a book which Alastair and friend Alex once tried to flog to a queue of Christians waiting outside a fellowship meeting. Atlas, as he put, was there to snap people’s minds, and he was a master prankster. Yet at the same time, Atlas had a social bump: snapping minds, yes, but at highly accommodating prices – and packed with as much content as possible. None of your experimental books where 30 boring pages are thinned out to make 120 with a modernist aura.

Actually defining the content of the Atlas list is more difficult. We tried time and again with only moderate success, from a few opening words in the anthologies, an introduction in the Black Letters compendium, a text Alastair wrote for Atlas Anthology 3 but scrapped, several attempts on our website… but ultimately the internal logic to Atlas and the delightfully bastard anti-tradition relied in the main on our personal chemistry: even at our peak of production during the 1990s, when we averaged over 7 books a year, Alastair and I reckoned we were in about 95% agreement on all titles.

Which reminds me: Alastair could be forthright on his views, presenting them without relent, but he could also be very open and considerate: he gave credit where credit was due, and sometimes went to unusual ends: he wanted for instance to publish a selection of stories from Rikki Ducornet᾿s book The Butcher᾿s Tales, so he sent me a copy and asked me to score each story from one to five, and after doing the same he published those with the highest overall scores: I think we only differed on one. But what a gentlemanly idea.

Alastair was a gentleman, an artist publisher, an epicure and beer-drinker, a book lover who would trash your books if you lent them to him, in short: a man of many parts who gathered around him many of the same; perhaps half of the Atlas authors were not only writers but also artists and/or composers, such as Alberto Savinio, Dieter Roth, Hermann Nitsch, Günter Brus, Hans Bellmer, and Jarry, of course. Or were also important scientists, doctors, psychiatrists, organ-builders, hormone researchers, jazz singers, computer scientists etc. etc. … which intriguingly brings us back to the programme Alastair and I had for that never published book in the mid-1970s.

But it is not as though we have come full circle, rather we are looking forwards and backwards at the same time. A few days ago I found in André Breton’s les pas perdus the words that “one publishes to find people, for no other reason.” But the opposite is also true, a lot of people found Alastair through Atlas. So even if we now have lost a person, a very wonderful one, a great deal of him has been found and will remain, found and unforgotten, because Alastair was pretty unforgettable.

Malcolm Green, February 2023

Forty Years of Atlas Press sadly also marks the folding of the imprint. Books will continue to be available through bookartbookshop, and they will be on sale at Small Publishers Fair 2023